My two weeks in China puts me in no position to tell China how they should change their education system or even how they should change the way they train teachers. After all, they have progressed more than halfway thought their extensive nationwide education reform efforts without my input. But, I feel I have enough background knowledge of education theory and enough real-world teaching experience to be considered an expert observer. That expertise, coupled with visits to a total of 14 classrooms in six schools, along with conversations with dozens of teachers and future teachers at least moves me up to the "listen to me" category. I may never reach the coveted "do as I say" status.

Classroom interactions

As I said in an earlier posting, most classroom interactions were from teacher to student. This is how most classroom knowledge was transmitted. A few interactions were from student to teacher, typically students answering a teacher question. Student-student interactions were non-existent in some classrooms, infrequently present in most classrooms and a significant part of only a few classrooms.

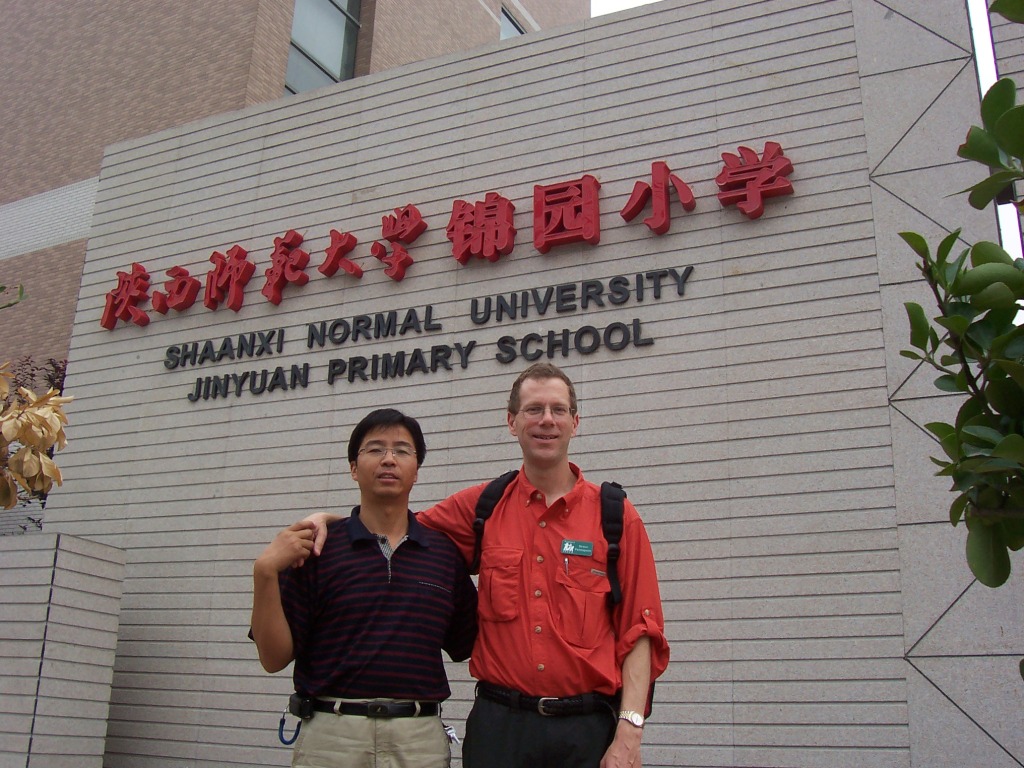

Here are my suggestions for Chinese Teacher Education programs, especially those that are relatively resource rich and opportunity rich such as Shaan'xi Normal University (SNNU). SNNU faculty members could read this and say, "Rich!? We need more of this. We are missing that." But, as one of only six normal universities directly affiliated with the State Educational Ministry, SNNU must see itself as the center of teacher education in Shaan'xi province.

- Provide teacher candidates with opportunities to work with children early and often. These experiences should be more than simply going to a classroom and observing. Every class I observed had SNNU students observing. But, none of those students participated in teaching the lesson. Having a large kindergarten and primary school right on campus and a middle school less than two kilometers away is a gold mine of opportunity for SNNU. SNNU students should help students in the classroom learn concepts. As the Chinese teachers more to a more inquiry-based curriculum, these extra hands, eyes and brains from SNNU will be very helpful, especially given China's large class sizes. I urge SNNU classes to partner with Shida K-12 classroom teachers to enhance the education of K-12 students. This partnership could start out as simple as one day a week for 15 minutes. Here is an example. For the last 15 minutes of class on Friday, SNNU students could teach a brief concept application lesson to a small group of primary or middle school students. If there are 60 children in a classroom, 20 SNNU students could pair up and teach a 15 minute lesson to 6 children each. Most classrooms I saw were large enough for the small groups to spread out. After the practical experience, SNNU students should be given the opportunity to reflect on their experience. A simple way to do this would be to answer the following questions: What did you learn? What went well? What could you improve? How could you improve it? Please note that this activity provides future teachers with many forms of feedback: peer, self, student, SNNU professor and K-12 teacher.

- Integrate inquiry teaching into every university class: teaching methods courses and content courses. Research shows students teach as they were taught. If a) every science course involved some inquiry, b) every teaching methods course involved inquiry, c) teacher candidates planned inquiry-based lessons, d) teacher candidates practiced those lessons, and e) teacher candidates reflected on those lessons, then graduates would be much more likely to teach using inquiry. Integrating inquiry into SNNU courses does not necessarily mean a major overhaul of a course. Hopefully that will happen in some courses. But, a simple and effective way to incorporate inquiry into a university course is to incorporate one to three questions throughout the lecture in which students must think about a concept, discuss the answer with their neighbor and share their answer with the class. This is called "Think, Pair, Share." Harvard University professor Eric Mazur has done this very successfully in his first-year physics courses. See http://mazur-www.harvard.edu/research/detailspage.php?ed=1&rowid=8 for more information. For more information about using the 5-E learning cycle as a means to plan inquiry lessons, see my blog entry, "All I Really Need to Know About Teaching I Learned in Shida Kindergarten."

- Help teacher candidates make incremental changes. New teachers are not ready to make large changes to the curriculum. Help them make the five minute change in year one that will result in increased student comprehension and retention. If they add another 5 minute change every year, coupled with a few major curricular changes, by year 10, they will have revised their whole curriculum. Here is an example I gave four Shida middle school English teachers interested in getting more students to participate in class. Put students into groups of four and number the students in each set of four 1, 2, 3, and 4. Write the numbers 1, 2, 3, and 4 on four popsicle sticks and put the sticks in a jar. Ask students to discuss a concept with their group of four. When the discussion is over, randomly pick a popsicle stick from the jar. Say, "I'd like to hear from a few students numbered (whatever you picked)". This method takes almost no preparation and forces all students to be ready to participate.